Methodology

After testing a small number of Sinclair (St. Clair and other variant spellings) family members worldwide, we noticed that we had several haplogroups present in our study who didn't seem to share a common ancestor until quite far back in time, some as long ago as 30,000 BCE. This led to many in our family voicing the oft-repeated thought that there was only one 'true Sinclair bloodline' and the others were the result of non-paternity events or folks in old Scotland taking the name of the laird. This notion is, in my opinion, the direct result of genealogists who seek to find one ancestor back in time for every member of the family who shares a name. Our Sinclair family is no different. The one supposed ancestor for our family has, for the last 200 years, been 'documented' as Rollo of Normandy. I suspected that the answer was not quite so clear cut as this and began looking for alternative hypotheses.

Hypothesis

My hypothesis is that, ours' being a name adopted from land in western Europe, some of our ancestors with wildly differing haplotypes might have found themselves living on the land in the period in which surnames were being adopted. If correct for even two of our lineages, this study will prove that our family origins are far more complex than traditional documents genealogy can resolve.

Alternatively, if the data leads to the likelihood that a

significant number of the family were not

in regions from which they could have acquired the surname during a

reasonable period in which surnames were acquired, then they must have

taken one of the Sinclair variant names from some other source, leaving

open the previously mentioned "laird" theory and others.

A second area of

study

Our family has many stories. You can see some of the more prominent

ones at the link at left - "Assessing Family Stories." I

immediately find

many of these stories doubtful but, approaching this

scientifically, this new science of genetics for genealogy might help

to shed some light on whether or not these stories have any basis in

reality. As you'll see at that link, I've spent less time looking for

data on these stories, but plan to focus more on this work after this

first DNA report is complete.

A Second Hypothesis

My hypothesis is that, when enough myths persist, there may be a grain of truth in them. There may be some basis in reality to the legends of our association with the Templars, a Holy Bloodline, the Prince Henry St. Clair stories about early voyaging to the New World, and more.

A Description of

the Study

DNA by itself is simply a string of 25 or 37 numbers. When compared to good documents research, or other data points, the numbers become much more meaningful. We currently have five lineages which seem to connect sometime within the last 5,000 to 20,000 years. This is not uncommon. I've looked into many different family projects and many of their lineages don't appear to connect until at least 25,000 years ago. Some don't connect for well over 70,000 years. Our family is lucky in that we have tremendous documents research back to circa 600 AD which gives us another data point with which to compare.

A DNA test measures the lengths of 25, 37 and (preferably) 67 markers, or alleles, which are specific sequences on the Y chromosome. By comparing these markers for different test subjects, it can reveal approximately how closely the test subjects are related.

These sequences of alleles are not found within genes and have no known genetic function. The reason it works for genealogical purposes is that the observed mutations, once they happen in an individual, are carried by that person's descendants forward in time and are like road signs along the way. The mutating alleles are neither harmful nor helpful; they simply happen now and then, and they persist because the body doesn't notice the difference. These persistent yet changeable variations are the markers that allow us to tell our lineages within a family apart and how far apart they may be.

FTDNA also tells each person tested which haplotype they are. In population genetics, individual haplotypes are classified into wide categories called haplogroups. This classification is based on different kinds of markers than those used in our DNA study. But FTDNA does tell us, especially with Deep Clade testing, what these markers are. Unfortunately, they provide little information about what they mean. Haplogroups are so broad that they are of little direct value in genealogy, but with a family as old as ours, I've found them useful in determining how and when our lineages got to Western Europe to take the surname from the land.

When you take the test, the results come back; I'm copied on them and begin to help you interpret what they mean.

The results and more at FTDNA

This is my personal entry page at FTDNA. You can see there is much to learn here. Down the left side, from top to bottom, (1) I belong to 3 user groups that are run by enthusiasts of these study areas. U5 is an mtDNA group that tries to answer questions about their background by having access to my results and my genealogy. There are many of these groups and they really are at the forefront of using DNA to solve ancient family history.

(2) is where I can submit my results to Ysearch.org, a group run voluntarily and made possible by FTDNA so those tested by other labs have a place to compare results. The "join" button allows me to join more groups as described above. The initials "WAMH" indicate that I'm part of the Western Atlantic Modal Haplogroup (see Glossary). (3) allows me to order deeper tests such as Deep Clade, CCR5-Delta-32, etc. This does not require further sampling as the samples are kept in a freezer in Arizona. (4) (User Preferences) allows me to control everything on the site. (5) (YDNA Matches) is extremely useful in allowing me to see those both in and outside the Sinclair family who I match (see the Name Matching study). (6) allows me to see where I might match others with the same recent ancestral origins, such as Scotland. I don't find this very useful as it relies on others to have good documents research and I'm always skeptical. By clicking (7), you'll see the chart to the right with my actual results. Those links between numbers 7 and 8 allow you to view and control your mtDNA results. (8) allows me to view Autosomnal results. This area is completely private, even from the project administrator, as it's related to mutations that allow us to be resistant to AIDS and the West Nile virus.

By clicking (7) from your FTDNA homepage, you'll arrive at the web page, shown below, which displays your YDNA results. These are mine. To protect the privacy of our participants, they're the only ones I'll fully display in this report. (1) shows my Haplogroup. If you've not taken a Deep Clade test, then the one they'll show here is their best guess. Without Deep Clade testing, you can't be sure, so I highly recommend you click that "Order Tests & Upgrades" link at the top left of your page and get further testing. (2) shows the results of my Deep Clade testing. These are the numbers that designate my SNPs. 'Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms'). Each SNP is a change in the DNA code at one single letter. These changes can be thought of as a fork in the road and are the way we identify specifically to which haplogroup we belong. Because people migrate over time, we can use these SNPs to trace where we were during specific times.

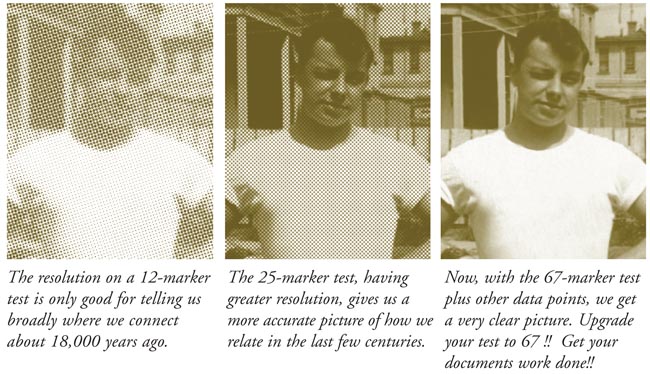

(3) shows my first 12 markers. This is usually the first set of results to come in from FTDNA and is not very useful to our study as it shows which group you may belong with about 18,000 years ago. (4) shows the next set of results that come in getting me up to 25-markers. This is the minimum you may order to belong to our study. (5) gets me up to 37-markers and now you can really begin to see some real differences in the members of our family and begin to understand why we differ.

Beyond (5) you can see I've gone all the way to 67 markers. I began to understand why this was so important when a consultant pointed out how careful FTDNA was in selecting the parts of the Chromosome that would be tested in this set of 30 alleles. This set contains many very stable markers and, thus, is very useful in understanding older connections (or lack thereof) between members of our family. It's critical that one or two members of each of our lineages test to this many markers and most of our lineages have.

It's the comparison of these haplogroups and the specific results that come back from FTDNA that make it possible for me to tell you so much about yourself and where you connect to the wider family. But it really comes alive if you've done your part - good documents research.

Keep in mind, the two charts you've just seen show our results from Family Tree DNA. I'm also having family members tested using other testing labs like EthnoAncestry.

A note on

continuing your testing.

I know how expensive this

is

for all those participating. Many in our project have never hesitated

to order new tests when I request it of them, no matter the cost. For

many others, St. Clair Research pays for further testing. The

illustration below clarifies why this is so critical in gaining a clear

picture of our family history.

How the numbers are used

DNA results are good for two things - (1) For helping to clarify recent genealogy from about the 1600's to modern day or (2) to clarify an individual's very ancient path out of Africa up until about 8,000 BC. so their line's geography can be better pinpointed to a specific region at a specific time. But when compared to linguistics (place names, first name conventions, etc), archaeology, pictography, etc., DNA experts are able to add clarity to where specific groups and SNPs were in time and geography. Then I'm able to compare your results to all these various findings and figure out where each of our members' ancestors was.

First, Number 1 - the documents - Number 1, above, may sound fairly easy. Take my word for it, if you think you have a rock solid paper trail back to the 1,400s or even worse back to Rollo, you're probably fooling yourself. I've just seen too many that can be disproved. In fact, I think every single documents trail in our family should be examined very carefully, every single one - yours included, and I'd like to talk about that a bit.

First, what documents did you base your genealogy on to get back to the 1600s and before? I've looked at all the published sources on our family and am quite comfortable shooting holes in all of them before the 1600s. If you study all the these books, they quote the same foggy ancient history going back to Rollo and this is their basic flaw - they seek to connect us all to one common ancestor. I talk more about this in our Book Review section (link at left). This DNA report proves that, at some point, these books are clearly wrong because we have several lineages and we don't all go back to one common ancestor, at least not until about 25,000 years ago or more. .

Second, do you have 2 sources for every single birth, marriage or death record? That's how good genealogy works. If you honestly can't say you have two records for each and every death, then you don't have a solid paper trail. We have a awful lot of people pointing back to the Earl's line, yet these peoples' DNA is proof that they don't connect until several thousand years at best.

Third, do you at least connect via DNA to someone else whose paper trail points in the same direction? And, VERY IMPORTANTLY, if you do connect on DNA and have your documents, was your documents work done independently? If not, you can bet it's a wee bit too convenient. Independent documents research is critical. Don't wait for someone else to do yours.

Second, Number 2 - the ancient path - Your DNA numbers will help me match you up to all the other work I've done to identify our Lineages. By tracing your likely path through time as part of a broad group, I can give you a good idea of where to continue to dig for documents at specific time periods. Or I can at least tell you roughly which geography your ancestors were in at a time just before documents were kept. As DNA testing advances and further SNP tests are invented, we'll be able to learn even more recent information about our participants. A great example of this is how I was able to pinpoint one of our lineages (DYS390=23) as the likely Anglo-Saxon Invaders of England, getting their geography pinpointed at sometime between 400-1,000 AD. This was a major triumph for me because it allowed me to narrow the window between Number 2 and Number 1 above down to a period of just 600 years. This is getting exciting.

What's a Lineage?

Different projects use different terminology to define their family groups. I call ours lineages. They're simply convenient ways to divide up your participants based on those alleles you decide may be best to define your different groups.

A family can divide themselves up any way they want. If you look online, you'll see some family projects that don't demand more than 12 or 25 markers to participate. This is, in my estimation, a weak way to do a family study.

Now you're reading about the very core of my study of the Sinclair family - lineages. The methodology of dividing up our family is the most critical part of the study and the most susceptible to criticism by other researchers. After many years of reading and researching, advice from outside experts and other study, I gladly invite the criticism.

After carefully studying our results for several years, I noticed that one allele in particular was consistent in our family - DYS390. This is a very stable marker and has been used as the basis for many studies by geneticists, like A.A. Foster and Heyer, to study broad human migrations in Europe. Thus, I made it the basis of our family study. Let me clarify that any marker can mutate at any time and we may have some folks who have mutated on DYS390, but you have to draw a line in the sand somewhere and I drew mine on this marker. That's where it started, and then I went on to classify our lineages using other markers and comparison to more studies.

I'm also dividing up our lineages based on other testing such as EthnoAncestry's S21. So while our S21+ members are technically part of the AMH, I classify them as a different lineage because I don't believe they have a MRCA for the period of recorded history, indeed, likely for about 3,900 years. You'll see how they divide up at the "Our Lineages" link at left.

When I divided up our members based on those markers known to be more stable, I was able to prove that my method of classifying our lineages was, in fact, the right way to do it. In this chart, those alleles highlighted in yellow are the more stable markers. We still ended up with five lineages and proved that our mutation rate is about normal with other humans.

Why we have five or more lineages

First, for years now I've heard all but one of the explanations listed below on our various family chat groups. Second, all but one of these pre-suppose that there is only one "true" Sinclair lineage and the rest somehow took the name for various non-legitimate reasons.

These are the possible explanations -

1. People fooled around back then like they do now and polluted our blood line - I find this almost completely absurd as a singular explanation for why so many of our participants don't belong to a single bloodline. While some surely did have relationships out of wedlock, they did not pollute a pure blood line. We've tested well over 140 people now and the sheer numbers almost certainly rule out the possibility that this theory accounts for ALL the differences from "one true bloodline." Our lineages are discussed in another chapter and, in that, I clarify why I think we've never had "one true bloodline." Non-paternity events, as these are called in the DNA world, likely account for some of our members with the same last name not matching any lineages' DNA. But I can't accept that so many of us, with good documents back to Scotland and beyond, are the result of ancient non-paternity events.

2. They took the laird's name - We have many good genealogists working on the history of our family. They can't all be wrong. Certainly some of our family took the name of the laird. The name matching project may yet prove which of us are affected by this.

3. Adoptions - We have some. Again, the name matching project and documents research are the way to solve this question. During times of war, adoption was common. And even in recent times, we have some.

4. A faster mutation rate than other humans - This sure would make it nice for all our participants, but I can't honestly say that we mutate any faster than other projects. There's not yet any way to prove this. I can say that Niven and Ian Clennel Sinclair's red marker mutation rate is about once every 300 years, but that's not fast. Stan and I share approximately the same mutation rate on our red markers.

YDNA vs. mtDNA

As you read through this report, you'll see an overwhelming focus on YDNA. The reason is easily explained. As I say many times, DNA is, in itself, merely a string of numbers. Its real power comes when compared with other data points. Anyone researching a female line back in time will become very frustrated with how difficult it is to find solid documentation of an unbroken female line back before the 1600s and 1700s. The reason is that males carried the surname and females may or may not have been mentioned by their maiden name in marriage or death records or, after marriage, the records of their children's births.

We opened the mtDNA project several years ago at the urging of several of our members. Unfortunately, we've so far learned almost nothing of Sinclair family history as a result. However, this part of our project could still prove very useful for solving questions of genealogy. If someone were to come forward with a relatively recent question of female-to-female genealogy for instance, under certain circumstances we could use mtDNA testing to solve it.

In this illustration, test subject F9, a female, wants to know if she connects to any Sinclair line. She suspects she does, as family stories tell of a g-grandmother who was a Sinclair. Through careful documents research, we could help her go back in time to 1888, then work her way forward, looking for an unbroken female-to-female line leading to a second living descendent of the marriage of M1 and F1. This chart shows the marriage of M1 and F1. Then to save space no other marriages, only the offspring. Example, husband of F4 is not shown, only their children F7 and M6.

As you can see, F7 is a descendent though her last name is not remotely close to Sinclair. If this woman F7 would agree to test, a connection between F7 & F9 would be proof, via mtDNA, that both descent from the marriage of M1 and F1. If F7 won't agree to test, the males M6 or M8 could be approached for mtDNA testing. F8 could not as she would not carry F1's mtDNA through her father M4, only her mother's mtDNA.

You may be wondering why M6 and M8, being males, could be tested for this study. A son carries his mother's lineage's mtDNA but does not pass it on to his son or daughter. Thus, a test of the male M7 would be useless as M4's wife (not shown), who is of another family, will pass her mtDNA to her son M7. Note that M9 carries M1's YDNA to the present day, though it's useless for testing F9's descent from F1.

Also, if the desire becomes to find out where F1 might fit into the wider family, and if she is a Sinclair, you must go further back in time to find a male uncle of hers, then work your way forward with documents research looking for a living father-to-son descendant of his to test with YDNA. The mtDNA of F1 will not tell you where this family fits into the wider clan. This kind of persistence, however, will tell you a great deal.

If any participants have questions as to whether mtDNA can solve their questions of genealogy, contact me and we'll discuss the possibilities. With an inventive use of mtDNA plus good documents research, such questions can be answered with absolute certainty.

Participants are sometime confused as to why we can't work back and forth from YDNA to mtDNA. Hopefully this mtDNA illustration helps to answer that question. Both mtDNA and YDNA are transferred in straight lines, one female-to-female (with the exception of sons getting the mother's mtDNA but never transferring it onwards), and YDNA transferring only father-to-son.

Thus, with documents (birth, death, marriage) focusing

primarily on the male surname, and with mtDNA focusing exclusively on

mother-to-daughter transfer, our project must focus mainly on the YDNA

to achieve our goals of understanding our ancient family history. But

don't let that stop you from using mtDNA to solve your questions of

female side genealogy.

Ongoing learning

Keeping up with all this is never easy. The best thing to do is to

befriend those on the front lines of DNA research, folks like World

Families, EthnoAncestry, and the specific SNP user groups. But the

single most useful thing I've done to add value to our numbers is to

join DNA-forums, the user groups that FTDNA makes possible. These folks

are really at the forefront of the research.

By looking at what they're doing, by continually pressing our members to test and upgrade their results, I'm always finding new data with which to compare your results. Because these folks are at the forefront, they tend to be careful and don't make a lot of breathless pronouncements.

How we learn from the results

As new members join our project, their results are visible to them and to me via a password protected part of the FTDNA website. Early on, I would enter them into our St. Clair Research website behind yet another password. Originally, my site allowed limited comparison between participants based on what I knew at the time.

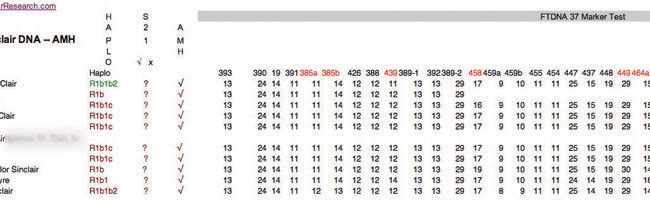

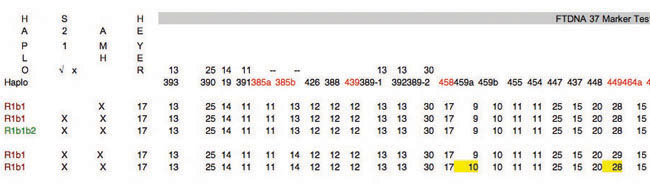

Early in the spring of 2008, I took advantage of the simple and elegant power of Excel software and now plug all results into that database. It allows me to very quickly compare all members of the project by selecting specific alleles and eliminating others. This has led to an entirely new understanding of our lineages and was one of the things that made it clear that it was time to publish this first comprehensive report. For instance, this is a chart generated by filtering by those 7 alleles that define the AMH.

As I learn about studies such as that done by Heyer, I can quickly compare all of our participants against the new data and see how we stack up. These results are in a separate attachment which will be shipped to the participants of our study, not to the general public.

Below is another example of how I sliced the full project using the Heyer Study of 1997, (82) I go into great detail about this study later but, here, it's useful to notice how few people within our project fell into the Heyer Study group called "DYS390=25 Haplotype #17."(83) As you'll read in that section of the report, I was able to make a startling statement about the path of the ancestors of some of our participants based on this finding.

Those numbers above highlighted in yellow are the key to our understanding. Those are mutated numbers off the main group. This person is showing a genetic distance of about 3 from other members of this lineage. I say "about 3" because two of the mutations are on red alleles that are believed to mutate at a higher rate than the others, thus allowing us to take them less seriously. A good example was the match between Niven Sinclair and Ian Clennel Sinclair. They are separated by a genetic distance of 3, but the alleles are all among the group known to mutate more quickly. That, plus the knowledge that they had good documents connecting them, allowed me to bend the genetic distance of 2 rule and place them in the same lineage.

Don't get the idea that the faster mutating markers are ignored in our study. In fact, the Ian Clennel Sinclair and Niven Sinclair connection above is a good example of just how useful they can be. The slower mutating markers are useful for establishing very ancient connections among our family members, or lack thereof. The red markers are extremely useful in further refinements among existing lineages.

That's the basic way the results are used. But to truly figure out our past and fully understand what our results mean for each of us, I had to go much further. Most people using DNA for genealogy just compare the results to the known documents trail and are able to reach conclusions about ancestry from the 1700's to the present. I wanted to know much more about our ancient family. So I had to go beyond the numbers.

Read our page at Family Tree DNA.

We're writing on Tumblr

One of our blogs for the Sinclair family DNA study

Another blog for our Sinclair DNA study